PRESS

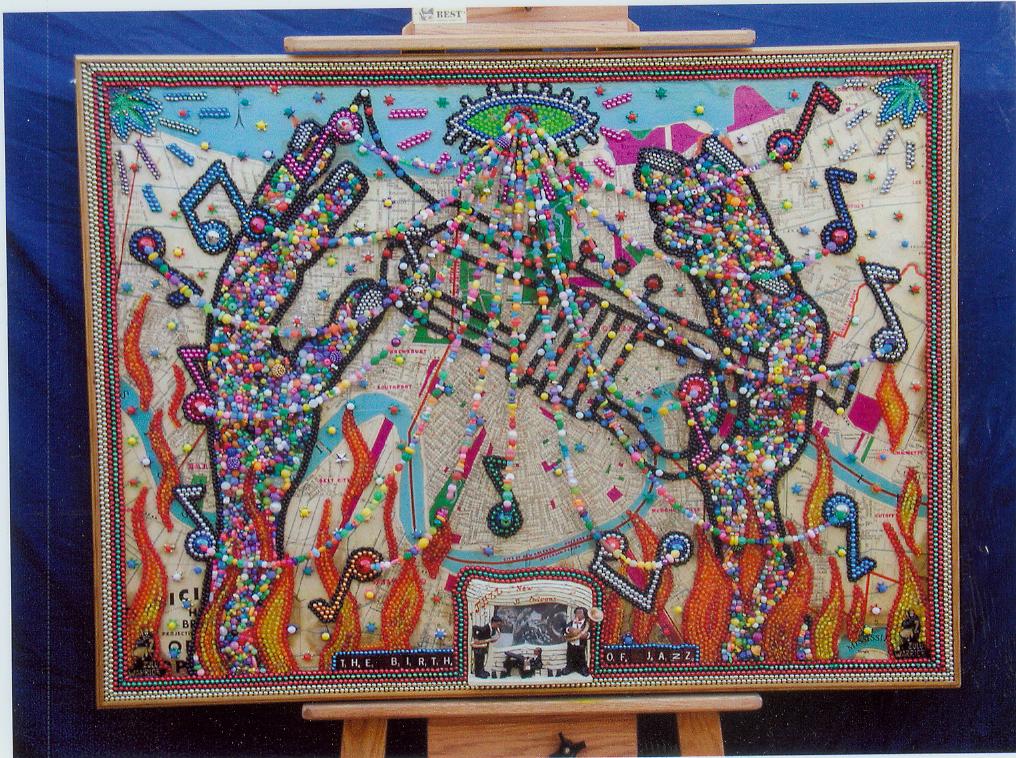

Heart of Louisiana: Mardi Gras Bead Art

One artist has spent years turning discarded beads into colorful, three-dimensional works of art

By Dave McNamara 3/6/2022 — Read original article here.

BATON ROUGE, La. (WAFB) – This is that time of year when bags of Carnival beads will be dumped into trunks, closets, attics, and even trash cans but one artist has spent years turning discarded beads into colorful, three-dimensional works of art.

After the Carnival parades have passed, streets are speckled with those colorful strands of plastic pearls that are broken or simply not snatched out of the air. It was that kind of post-parade scene in New Orleans that inspired artist John Lawson.

“I was looking out the avenue and the trees and it just looked like this mosaic of color and beauty,” said Lawson.

His journey from his native England landed him in the Landscape Architecture School at LSU.

“Fell in love with Louisiana and stayed,” added Lawson.

Continue reading...

But art became his life’s work. Lawson would scoop up shopping carts full of beads along parade routes. And those beads became the raw materials for his mosaics. And naturally, many of his creations focus on Louisiana and Carnival and colorful traditions like Mardi Gras Indians.

“The idea is that it’s him in costume like dancing towards us,” noted Lawson.

The bead art has a three-dimensional form.

“So right now, I’m just laying in the initial colors and then I will get back behind it and clean it all up,” explained Lawson.

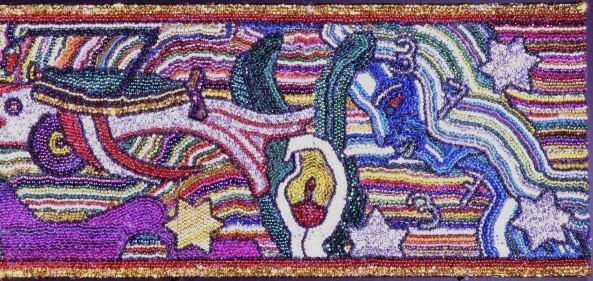

He calls one of his works still in progress, ‘Big Mamou.’ It is a celebration of the colorful Mardi Gras riders who gallop across Cajun Country.

“It looks like the horse is moving,” described Lawson.

The process is time-consuming. It involves using a special formula of hot glue, adding strands of color, and then filling in any space with smaller beads.

Lawson calls another piece, ‘Floodline.’ It’s a reference to the scars that Hurricane Katrina left on New Orleans and holds personal photographs that were ruined by the flooding.

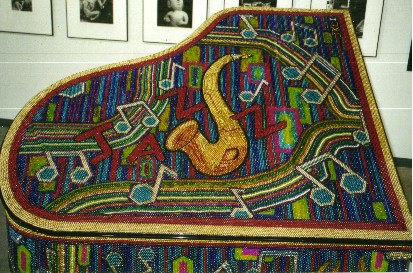

Lawson’s canvas can be unconventional, like a baby grand piano in the Voodoo Two Lounge in New Orleans.

“My work consists of getting to the bar at 8:00 in the morning when the people were cleaning it and sit down and start working on this piano. And then, I would go home at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning when they were closing up, so these pianos take about three months,” said Lawson.

Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau comes to life with beads above, below, and all around the black and white keys, covering every inch of the piano.

I generally take it to an automobile body shop and they lacquer it up,” added Lawson.

It’s a spectacular use of left-over Carnival beads that creates colorful characters and a lasting impression of the fun, the excitement, and the whimsical nature of Mardi Gras.

Copyright 2022 WAFB. All rights reserved.

Mardi Gras Beads

From the Street to the Gallery

By

Mardi Gras beads litter the streets and sidewalks of New Orleans after the parades have passed. The colorful strands of plastic pearls lay broken on the pavement, the result of missed catches from the overwhelming barrage of throws from an endless stream of Carnival floats.

The post-parade scene of unwanted Mardi Gras beads inspired artist artist John K. Lawson. He recalls a walk along St. Charles Avenue after a parade, “It was really a bright afternoon, and it just looked like this mosaic of color and beauty.” Lawson, a native of England, attended the Landscape Architecture School at LSU and never left Louisiana.

mardi gras beads become art

On the day I visited Lawson’s studio located near Baton Rouge, he was using a hot glue gun to attached multi-colored plastic pearls to a horse head shaped figure. He calls this new work “Big Mamou”, a celebration of the colorful Mardi Gras riders that gallop across Louisiana’s Cajun country. (see story here).

An unconventional canvas

Continue reading...

One of Lawson’s creations is on display in the front window of the Voodoo Two Lounge on Carondelet Street in downtown New Orleans. Beads cover nearly every inch of the baby grand piano in a dazzling tribute to voodoo priestess Marie Laveau. The black and white piano keys are the only surface without beads because Lawson doesn’t want to interfere with playing the piano.

mardi gras beads and hot glue

Beads attached with hot glue gun

The process is time-consuming. Lawson uses what he calls a special formula of hot glue to attach strands of beads. Then he fills in any open spaces with smaller beads. “Once the piece is finished,” Lawson explains, “I take it to an automobile body shop and they lacquer it out.” He wants the beaded creations to last as long as whatever it’s attached to.

Lawson’s art is a spectacular use of left-over carnival beads. He creates colorful characters and pieces that preserve the fun and whimsical nature of Mardi Gras.

Mardi gras bead art featured on tv

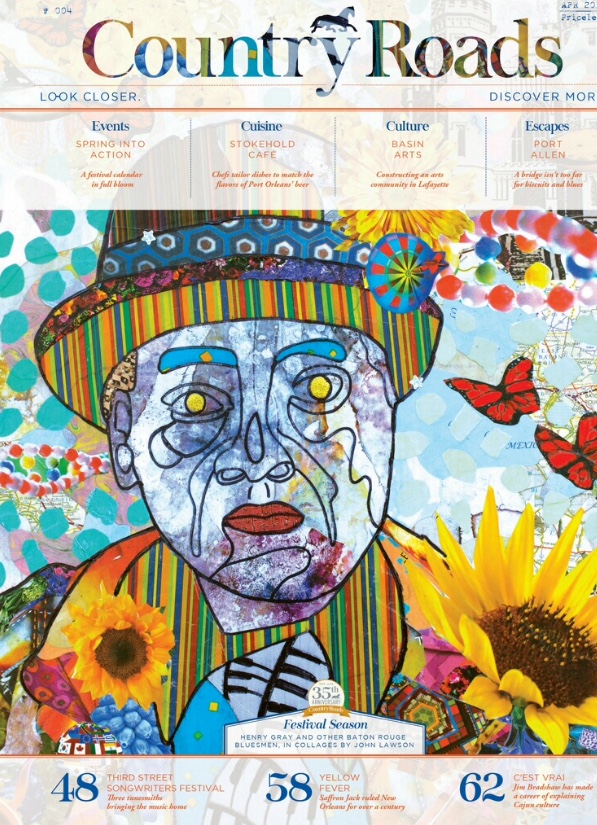

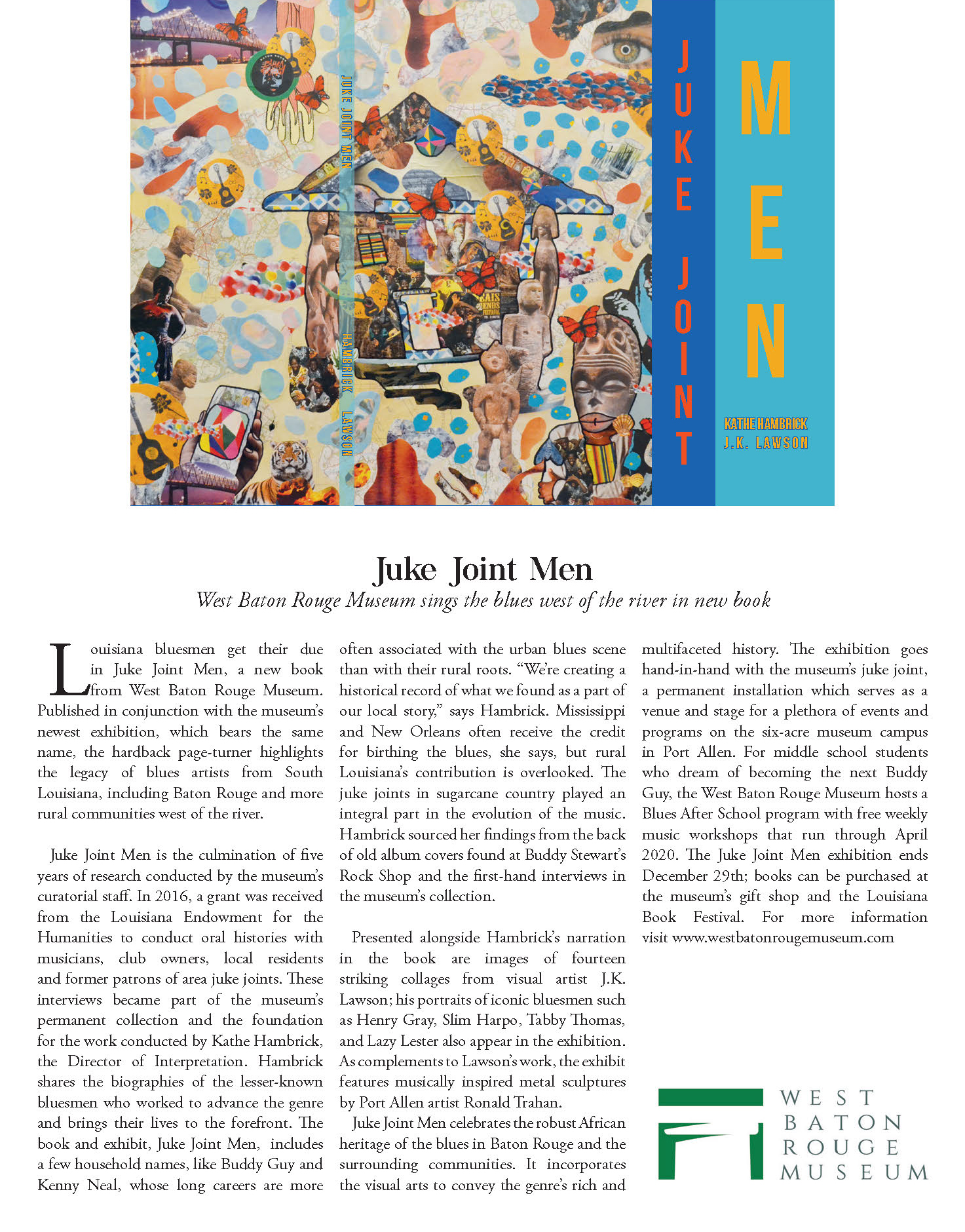

Juke Joint Men

West Baton Rouge Museum sings the blues west of the river in new book

11/2019

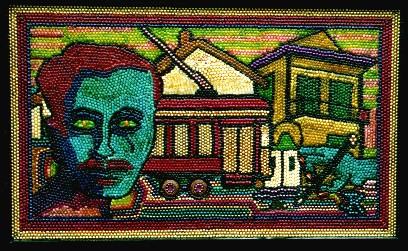

Louisiana bluesmen get their due in Juke Joint Men, a new book from West Baton Rouge Museum. Published in conjunction with the museum’s newest exhibition, which bears the same name, the hardback page-turner highlights the legacy of blues artists from South Louisiana, including Baton Rouge and more rural communities west of the river.

Juke Joint Men is the culmination of five years of research conducted by the museum’s curatorial staff. In 2016, a grant was received from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities to conduct oral histories with musicians, club owners, local residents and former patrons of area juke joints. These interviews became part of the museum’s permanent collection and the foundation for the work conducted by Kathe Hambrick, the Director of Interpretation. Hambrick shares the biographies of the lesser-known bluesmen who worked to advance the genre and brings their lives to the forefront. The book and exhibit, Juke Joint Men, includes a few household names, like Buddy Guy and Kenny Neal, whose long careers are more often associated with the urban blues scene than with their rural roots. “We’re creating a historical record of what we found as a part of our local story,” says Hambrick. Mississippi and New Orleans often receive the credit for birthing the blues, she says, but rural Louisiana’s contribution is overlooked. The juke joints in sugarcane country played an integral part in the evolution of the music. Hambrick sourced her findings from the back of old album covers found at Buddy Stewart’s Rock Shop and the first-hand interviews in the museum’s collection.

Presented alongside Hambrick’s narration in the book are images of fourteen striking˜collages from visual artist J.K. Lawson; his portraits of iconic bluesmen such as Henry Gray, Slim Harpo, Tabby Thomas, and Lazy Lester also appear in the exhibition. As complements to Lawson’s work, the exhibit features musically inspired metal sculptures by Port Allen artist Ronald Trahan.

Juke Joint Men celebrates the robust African heritage of the blues in Baton Rouge and the surrounding communities. It incorporates the visual arts to convey the genre’s rich and multifaceted history. The exhibition goes hand-in-hand with the museum’s juke joint, a permanent installation which serves as a venue and stage for a plethora of events and programs on the six-acre museum campus in Port Allen. For middle school students who dream of becoming the next Buddy Guy, the West Baton Rouge Museum hosts a Blues After School program with free weekly music workshops that run through April 2020. The Juke Joint Men˜exhibition ends December 29th; books can be purchased at the museum’s gift shop and the Louisiana Book Festival. For more information visit www.westbatonrougemuseum.com

Entremares Magazine

John K. Lawson: From the ruins, a rebirth

05/2014

By Betty Aguirre-Maier

In August of 2005, Hurricane Katrina pummeled New Orleans, leaving John K. Lawson’s house and studio under nearly 10 feet of water for six weeks. The storm changed the British artist’s life, setting a before and after nonetheless infused with optimism for art and life.

Lawson grew up in the English countryside, where he came into contact with gypsies and transients who came to his home looking for work or food. Their skin, weathered by countless wandering days, and the texture and craftsmanship of their intricate clothing fascinated his young, artistic eye. From them, he acquired a unique sense of place and space, and a nomadic mindset. This, as he would later learn, had a profound effect on his life: his decision to move to the Deep South, to New Orleans, a true melting pot of French and African-American heritage, and how years later a catastrophic storm would force him to rebuild his life and move again.

Before Katrina, Lawson was known for his intricate works using discarded Mardi Gras beads. At night, when the carnivalesque exuberance waned and the city slept, Lawson would wander down St. Charles Avenue and collect the beads, which became the building blocks of extraordinary art pieces, such as a piano completely covered by the colorful beads. But beyond their aesthetic beauty, these pieces are charged with political and social commentary.

After Katrina, Lawson moved north, where he divides his time between the cityspace of New York and the rural life in his home in Massachusetts. Here, he begins a new chapter filled with new memories, characters and life, the product of which are published here.

These pieces, which Lawson has spent the past five years working on, are enveloped in a mystic aura, impregnated with energy and intricate details. Painted paper, newspaper, magazine and catalogue clippings are the raw materials that Lawson employs to construct characters that appear and disappear in a fragmentary play of color and form. Iconic figures of the jazz scene such as Ella Fitzgerald, John Coltrane and Charlie Parker seem to emerge from the stupor of an endless party, of a perpetual carnival that celebrates life. The spectator can’t help but feast on the colors, the constant movement, and surrender to Lawson’s call to life.

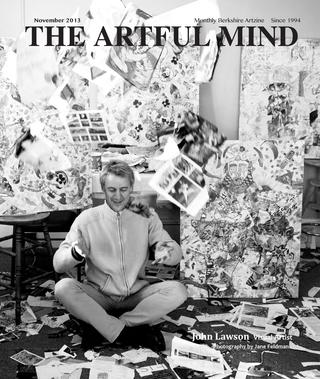

The Artful Mind

John Lawson: Visual Artist

11/2013

Interview with Stephen Gerard Dietemann

Photos by Jane Feldman and Jonathan Hankin

Bard College at Simon’s Rock

October 22-December 21, 2007

JOHN K. LAWSON / FRAGILE

One morning in Maine, John Lawson took a dingy from the island where he and his wife were vacationing to the mainland to fetch the morning paper, and learned that his home and studio were under six feet of water and that his adopted home city of fifteen years was in a state of chaos. It was six weeks before they were allowed to return to New Orleans and sort through their personal belongings. Everything was damaged. From his studio drawers Lawson pulled out twenty-five years’ worth of soaked sketches and drawings. By pulling the paper carefully apart he laid what was still intact onto the porch of a friend to dry in the sun. The piles of photographs though were less salvageable; in some the subject was still discernible, but for most the colors had bled into one another, creating abstractions in brilliant colors, which melted and crept eerily across the faces of family and friends. With these remains, about a third of his life’s work, Lawson began his journey of understanding the disaster that had changed his life forever. In this exhibition we are witness to Lawson’s mourning, healing and ultimate discovery of acceptance and hope.

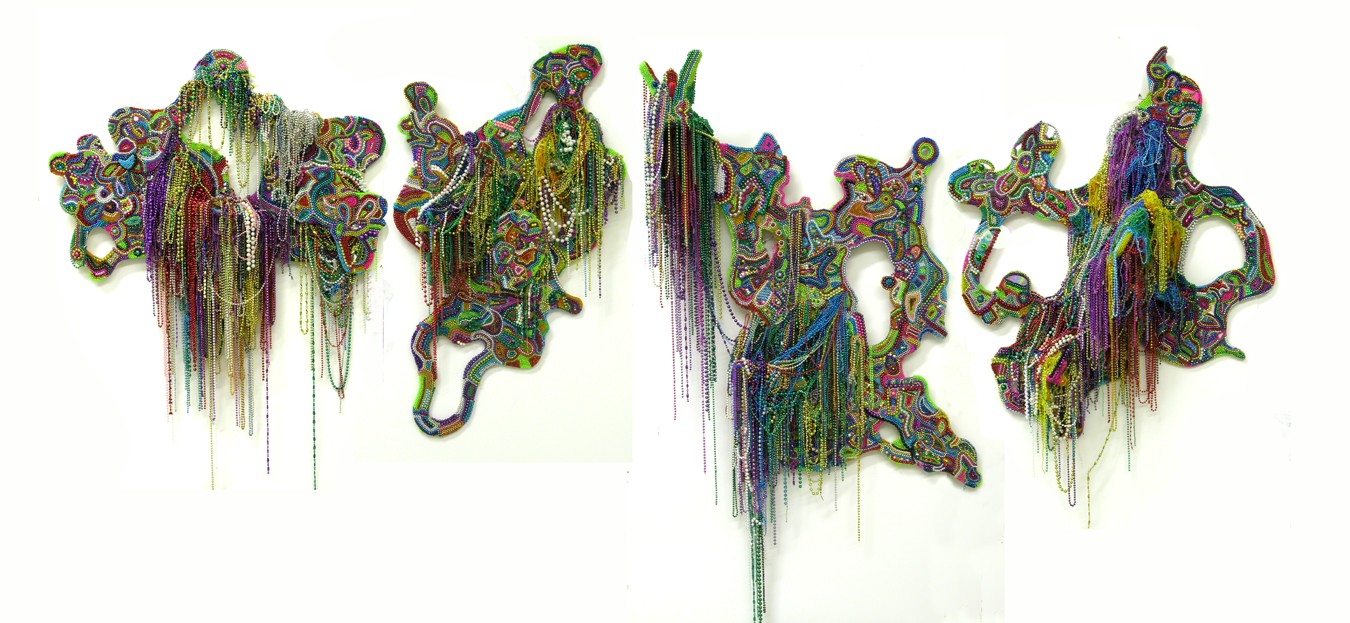

Fragile, Lawson’s first exhibit in the Berkshires, consists primarily of three bodies of work: beading and tattoo drawings, explorations with digital photography, and flood-salvaged, reworked drawings with encaustic wax.

Before Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, Lawson’s primary medium were his trade mark Mardi Gras beads, picked up from the streets of New Orleans in the early mornings after the parades and parties. The creative and unique ways he used the beads is exemplified in War of the Worldz and Icarus. These works not only show Lawson’s meticulous and labor-intensive beading method, but also speak to his view of materialistic consumerism and his full-blown immersion and fascination with the under-culture of the city.

Soon after Katrina, Lawson began Floodline in a borrowed NYC studio. Using solely beads and photographs salvaged from his studio, he placed a long horizontal row of family snap shots six feet high (the floodline in his home), covered them in wax and then vertically placed hundreds of rusting strands of beads over them. Relieved to be safely out of New Orleans, but feeling displaced, Lawson needed to create something that captured the essence of the city for him. He used the beads as a memorial to its Mardi Gras fame, and the photos as a memory of an everyday life there. However, the “everyday” is now so changed and damaged that it must be approached carefully through a curtain, each image a fragile icon to discover and revere.

After using his water-damaged work to memorialize his now “lost” past, Lawson began to explore ways to transform those remains into new work. Embracing the photographs that the flood waters had altered out of his control he went back and manipulated the images himself. Through the digital photograph, a new medium for him, Lawson focused and enlarged areas of water-soaked, color-blurred photographs. In Beneath the Skin (I-II) he zoomed in on particularly striking sections of colors melting into one another and then, in defiance of the chaos, he mirrored the image with itself. In this simple act Lawson created balance and thus the perception of order. From the ruins he has pulled out harmony and invokes serenity.

Lawson most deeply explores his sense of loss and memory through looking at his past in a large piece entitled Tempest. A recent work created during a summer residency at the Santa Fe Art Institute, Lawson painstakingly retraced hundreds of salvaged sketches and drawings after pasting them in a collage onto nine panels. Lawson quite literally “connected the dots” of his life by not only redrawing each line but by embellishing the sketches and connecting one to another. With each piece of paper he encountered, Lawson relived a memory. His work on this project was so captivating that a colleague filmed Lawson drawing for eight straight hours during his residency in Santa Fe (the whole retracing took over one hundred and forty hours). Finally, using the encaustic wax process Lawson sealed each panel in several layers of translucent brownish wax, first outlining the sphere of the moon, then filling in each circle to represent a different phase of the moon. The moon here not only symbolizes the rebirth of New Orleans (often called the Crescent City) but also Lawson’s own acceptance and growth since the disaster. The phases of the moon quietly move across the pages of his life, rhythmically and predictably. Tempest is a testament to the persistence of time propelling us into our future where, ultimately, healing will begin.

Margaret Grant, Curator, October 2007

About the artist:

John K. Lawson was born in Birmingham, England, in 1962 and raised mostly in the countryside until his family moved to South London when he was a young teenager. He first came to America on a student exchange program in engineering at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. There his artistic abilities were encouraged, and he returned to England two years later to concentrate on landscape painting. Eventually, Lawson was drawn back to the Deep South, and soon became part of an underground art culture in New Orleans that included working in tattoo, T-shirt and mural designs long before these mediums became mainstream. Lawson also became known for his unique drawing style and creations using discarded Mardi Gras beads. He covered mannequins, pianos, and drums with intricate bead work, including a fifty-three-foot- long bar top at the notorious artists’ haven, the Audubon Hotel. Since Hurricane Katrina, Lawson divides his time between studios in New York City and Great Barrington, where he lives with wife Aimée Michel and their five year old son, Sebastian.

The Simon’s Rock Exhibitions Program oversees a series of changing exhibitions of professional artists, faculty in the arts, alumni artists, and art students on campus within the Library Atrium Gallery, the Daniel Arts Center, and the Gallery at Liebowitz. The program seeks to have an academic and curricular component where students and artists are engaged through artists talks, workshops, and installation participation. All the galleries are open to the public, handicapped accessible and free of charge.

The Curator would like to acknowledge those whose collaboration and support made this exhibition possible: Danae Boissevain, Lauren Crispell, Joan DelPlato, John Lawson, Juliet Meyers, Judith Monachina, and Dan Romanow.

Bard College at Simon’s Rock

84 Alford Road

Great Barrington, MA 01230

413-644-4400

www.simons-rock.eduExhibitions Curator, Margaret Grant, 413-528-7389

mgrant@simons-rock.eduThe Gallery at Liebowitz is open daily 12-5

All photos courtesy of the artist.

Lagniappe News

APOCALYPSE N.O.

Carnival beads create John Lawson’s sci-fi nightmares

06/14/02

By Doug MacCash Art critic

Artist John Lawson, whose exhibit “The Second Coming” is on display at Barrister’s Gallery, sees the future. In his vision, the world has gone terribly wrong: Strange biologically engineered monsters with the bodies of dinosaurs and the heads of human children stalk the earth, psychedelic space creatures are on the attack, flying saucers hover in the sky and everything, everywhere is covered with . . . Mardi Gras beads.

In the past few years, Lawson has perfected a style of meticulous Mardi-Gras-bead mosaic, which he’s used to decorate objects such as the bar top of the pre-renovation Audubon Hotel and an upright piano (both are included in the exhibit). He’s also created more conventional two-dimensional mosaics, such as portraits of Louis Armstrong and Tennessee Williams. Lawson’s colorful beaded works have always been entertainingly kitschy, if a bit superficial. With his new suite of mosaics, though, he proves that he’s capable of digging beneath the surface into a surrealistic science fiction world that’s as frightening as it is amusing.

In “Ritalin,” a giant bird-like creature lowers a bottle of Coke to a suburban mom, as the face of Harry Lee smiles down from the heavens. In “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” sand-colored toy soldiers blast away ineffectively at an amorphous monster that is bearing down on a golden cathedral. In “waroftheworldz.com,” an anachronistic Spanish galleon crowded with babies defends the planet against laser-shooting marauders. And in “Emperor of the Universe,” five disembodied fingers hold the glowing face of — who else — Ernie K-Doe above mother earth. Star Wars figurines, magnetized refrigerator letters, king cake babies, Burger King promotions, kewpie doll faces and innumerable other dime-store plastic baubles all get into the act. Sure, Lawson’s works are silly, but they’re also beautifully composed, poetically topical and rich with symbolic meaning.

The Mardi Gras throws that are Lawson’s principal medium are supposed to be discarded after Fat Tuesday and forgotten in Lenten piety. Instead, Lawson uses these ephemeral symbols of earthly overindulgence to create permanent nightmares. The future according to Lawson is a cheap, garish, made-in-China, cosmic disaster — apocalypse New Orleans.

THE SECOND COMING

By John Lawson

What: Surrealistic Mardi Gras bead mosaics.

Where: Barrister’s Gallery, 1724 Oretha Castle Haley Blvd., 525-2767.

When: Tues-Sat, 10 a.m. to 5, through July.

Prices: From $150 to $2,800.

06/14/02

© The Times-Picayune. Used with permission

The Baltimore Sun

October 16, 2002

AVAM Just Says Yes to the Art of Addiction

By Mike Giuliano

High on Life: Transcending Addiction

At the American Visionary Art Museum through Sept. 1, 2003

Raymond Materson knows all about getting high. Back in his cocaine days, his obsessive need for drug money prompted him to try pulling off a parking-lot stickup with a toy gun. The ill-conceived venture landed him in prison, where he started to make two-by-three-inch embroidered pictures out of thread from unraveled socks.

In the end, not only did Ray Materson kick his drug habit, but after his release he became a drug counselor. Besides working with troubled, drug-prone youths, he still makes those tiny pictures, detailing scenes familiar to him such as going before a parole board.

Materson is one of the 100 artists in High on Life: Transcending Addiction, the latest mega-show at the American Visionary Art Museum. Like its subject, this large and obsessive exhibit has an addictive quality. You can easily get hooked in, for instance, by the textile-hooking skills that go into Materson’s mini-pictures, which cram up to 1,200 stitches into a square inch. While most of the featured artists only have one or a few works in the show, Materson rightfully gets a gallery to himself. He calls his embroidered autobiographical sub-exhibit “Sins and Needles.”

Walking through his show-within-the show during a press preview, the 48-year-old artist retraced his life’s journey and described how he felt when he first went behind bars: “I got to prison and I was angry at the world. I was angry at my creator and at the system that sent me here. . . . Then I realized I was at the bottom of a barrel and I turned myself over to God . . . and I was inspired to try this embroidery.”

Thinking about happier topics, like his grandmother and his beloved Yankees, Materson at first embroidered cheerful pictures of what he missed about his life on the outside; after his release, he dealt more with the imagery and events that marked his time in prison. The process clearly has been therapeutic for him.

“The embroidery was very time-consuming, and it gave me time to reflect on my past–things that I’d done wrong, yes, but other things I’d done right,” he says. “Out of this came a sense of healing. . . . Patience is never my strong suit, but I learned that you could learn patience.”

Soon, Materson says, the making of art became a source of comfort. “I don’t think I became addicted to it, but it became for me a new life source,” he says. “There was a certain obsessiveness to it. It was addictive, not in a dulling kind of way, but it was more of a freeing up. As I lost myself in the work, my thinking about myself became more clear.”

Materson is characteristic of many of the self-taught artists in this show, curated by Tom Patterson: The artist went from an obsessive compulsion to no-less-obsessive artwork that served to document both his addiction and his recovery.

All the drug references you’d expect are here, with heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, and other drugs featuring prominently in the imagery and accompanying text blocks. And to an extent, the exhibit has a polemical agenda: One text block refers to former Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke’s attempts to have us consider addiction more as a health problem than a criminal issue. That sentiment is presumably behind the exhibit’s inclusion of work that deals with other, more legal cravings, such as those for cigarettes, alcohol, and gambling.

Even with this thesis wafting through the air, though, the exhibit isn’t rigidly agenda-driven. Nor is it rigid in its definition of outsider art. In addition to many self-taught artists–some addicts, some not–who often toiled in obscurity far from the gallery mainstream, the exhibit also includes several professional artists and other prominent figures, such as the late writer William Burroughs, who certainly knew something about drugs.

Much of the work in the show’s opening gallery makes a point of presenting drug addiction as a particularly nasty business. Mark Henson, whose curriculum vitae includes using a lot of LSD in San Francisco, offers a painting titled “Illusion of Reality,” which depicts a man in bed having a literal pipe dream. In the smoke above his bed appear nude women in an idyllic, pastoral setting. But his dream state stands in stark contrast to his actual surroundings: a bedroom table covered with drug paraphernalia; a TV set broadcasting images of a nuclear explosion; and a view through a nearby window of a honky-tonk street scene in which prostitution and violence are the norm.

Similar themes are touched on in different ways elsewhere in the opening gallery. Leroy Almon’s paintings “Ghetto” and “The Old Gambler” depict slavish devotion to alcohol and gambling through the simplified realism one often finds in folk art. More overtly nightmarish is William Allen’s welded steel sculpture “Boogie Man,” a long-limbed monster that may be enough to scare you straight.

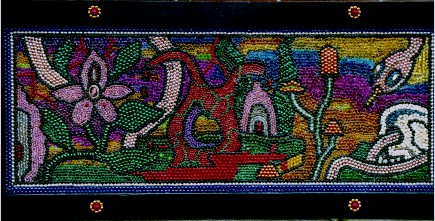

Other artists don’t go for such obvious horror-show effects, instead making more decorative artwork whose time-consuming craftsmanship surely factored into their getting their minds and bodies off drugs. For “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” for instance, artist John Lawson used colored Mardi Gras beads to create an elaborate mosaic that covers a 53-foot wooden bar top from a New Orleans saloon. For “Temptation,” he did the same to a piano from an old brothel.

Pieces such as these demonstrate how craft traditions–and the discipline they often demand–helped to spiritually save artists like Ray Materson and John Lawson. It’s a point perhaps most compellingly made in Tom Fruin’s “Treasure Map,” a large quilt made out of small, colored plastic drug bags the artist found on the street.

The final section of the exhibit, however, while meant to be uplifting, comes off as more problematic. If most of the artists seen in earlier phases of the show have put their addictions behind them to go on to more productive lives, the concluding rooms contain work by artists who use drugs in the belief that mind-altering substances help bring out their creative energy.

This case is agreeably made with examples relating to the shamanic use of organic hallucinogens, such as the embroidered designs and plastic beaded bowls of the peyote-consuming Huichol in Mexico. But the argument is much less effective in works such as Maura Holden’s painting “Thanatos Wave.” In her accompanying text, she uses words like “sacrament” and “self-discovery” to describe how hallucinogenic drugs inspire her. And her painting certainly looks like it was made by somebody who’s high. Its circular format contains a riotous, swirling mass of fantasy architecture and creatures, like a poster image you would’ve found in a late-1960s dorm room. Although the painting is technically competent, like other works in this section of the show, it’s not particularly interesting, even as psychedelic kitsch. It may be a head trip into the subconscious, but in a consciously co modified manner. It seems less like Hieronymus Bosch, in other words, and more like plain bosh.

The LENIN Exhibit

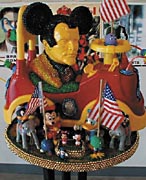

LENIN BUSTed was the brainchild of art impresario Andy Antippas, who acquired a bust of the dictator and had plaster replicas made to see what artists might do with them. Local artists rose to the challenge of turning an icon of collectivism into an object of individual expression. Most of their variations are as zany as Lenin himself was severe.

Artistically “messing with Lenin’s head,” artists have, among other things, adorned the Communist icon with Mickey Mouse ears, placed him in a red plastic bumper car along with American flag-waving Mickey, Minnie and Donald Duck; turned his head into a red, white and blue piggy bank and an eight ball; and have written script on his face.

“Gambit” reviewer D. Eric Bookhardt said the exhibit expresses, “an art community’s judgment on censors, dictators and control freaks of all stripes.”

by Christina Chapple SeLU.edu

John Lawson’s Inauguration of Lenin World, Moscow is the late communist dictator’s

John Lawson’s Inauguration of Lenin World, Moscow is the late communist dictator’s

worst nightmare realized, a sad take on the creeping global economy.

D. Eric Bookhardt, Gambit Weekly

The New Orleans Times Picayune

The color’s the thing for bead artist

11/09/01

By David Cuthbert Theater critic

John Lawson would seem to be an artist of extremes. Actually, he’s followed a black-and-white garden path down a rabbit hole into a Technicolored wonderland.

His work has covered a wide range of styles and approaches, but in the early ‘90s he was doing intricate, exotic, black-and-white pen-and-ink drawings; flowing, maze-like images that evoke Oriental and Mayan art and ‘70s psychedelia. The black ink gives these works a formality somewhat at odds with the impudent, surreal and sexual subject matter in his line labyrinths.

He didn’t use color for them, Lawson says, “because I couldn’t find anything to paint the drawings with that gave me the kind of color that I wanted. I didn’t find colors vivid enough until I started using Mardi Gras beads.” He pointed to a shiny expanse of vermilion beading on one of his works. “Look at that red there — you can’t get that any other way, not in oil, not in acrylic.”

The collection of 25 brilliantly beaded Lawson works now on display at Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre during the run of “Art” lights up the lobby with a blaze of sparkling color and constitutes a first-time, five-year retrospective for the artist. With the addition of the pen-and-ink drawings and crayon sketches for finished works, it also takes you on the artist’s journey to his current medium.

Le Petit historian Carolyn Barrois, who hung the show, said Lawson’s work “looks like Peter Max jewelry,” as indeed it does. But his art doesn’t just dazzle in decorative fashion with a shiny surface sheen, it uses colored Carnival beads to give depth and shading. He also encloses the works in his own frames — multi-colored borders of beads. The art shares a kinship with Mardi Gras Indian costumes, which often tell a story in much smaller beadwork and with the hot Haitian colors of sequin art. “Blue Desire,” his moody portrait of Tennessee Williams (shown below) ,greets theater-goers at the box-office. The playwright’s face dominates the surface, executed in an intense turquoise against a red streetcar and Vieux Carre backdrop. On the opposite wall is a crayon sketch of Williams, the model for the finished work and an illustration, through juxtaposition, of the heightened effect the beads can give a subject.

In a similar vein is “N’Awlins Trinity,” an alcoholic still life of a Hurricane, Bloody Mary and a martini, seen in a tryptych: crayon drawing, glittering finished work and as it appeared on a magazine cover.

“Marie Laveau” conjures up an Egyptian sarcophagus, with the black mannequin face of the voodoo queen rising from a New Orleans cityscape in flames, Dambala the snake god curling about her body, sacrificial chicken at her feet.

Lawson’s artistic heroes show up in his work: artist Freda Kahlo in two “Mexican Landscape” pieces, a William Burroughs tribute, “Satchmo” (shown on right) and “Big Chief.” Favorite insects (ladybugs) and bayou denizens (from the time he spent living in a cypress swamp in Sunshine, which inspired the shimmeringly beautiful “Swampsong”) reappear in his works. Hands are usually reaching out, and the beadwork paintings also delight in phallic facsimiles.

Lawson “paints” musical instruments with beads — a guitar and drum are here — and has beaded pianos, both uprights and a grand piano, the latter in Ralph Brennan’s Disneyland restaurant, a perfect setting for a playful Lawson piece.

There’s a kitschy element to his beaded bathroom scales, and a family of mannequins, some missing limbs (“because that’s the way I found them”) presided over by what appears to be a dominatrix Mommy. Its title is “Meet the Folks.”

His most arresting mannequin pieces are two demonic cherubs, antiques with glass eyes and lashes, painted ebony, with green and gold beading on their wings extending in swirls onto their thighs and legs, horns sprouting from beaded caps. They’re disturbing little guys, but amusing, too, especially in the context in which they’ve been placed: They’re perched on a sideboard, on either side of a portrait of Mrs. James Oscar Nixon, the doyenne who was one of the founders of the Drawing Room Players, which became Le Petit Theatre.

“When I saw John’s beadwork paintings,” said Shelley Poncy, who’s directing “Art” at Le Petit, “I told him how much I liked them and he said, ‘Well, you know, people look at this and say, “Yes, but is it art?” ‘ And since that seemed to be the exact conversation that’s going on in the play, I thought it would just be perfect.”

“Being a visual artist,” Lawson said, “maybe being any kind of artist — is to experiment, create a new way of looking at something.

“I’m really painting with beads. They become like a tube of paint for me. And the great thing is I never have to pay for them. I’m out there wheeling a little trolley after parades, scavenging, recycling the discarded treasures of Carnival.”

In his two-level Toulouse Street studio just around the corner from the theater, the 39-year-old, British-born Lawson displays some of his work-in-progress, such as a just-begun tribute to the late singer Ernie K-Doe. There’s also his major bead opus, his own idiosyncratic version of Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights,” (below)

with a myriad of fantastic and ordinary creatures and phenomena. Until recently, it was the bar top at the old Audubon Hotel. Times-Picayune art critic Doug MacCash says that in it, Lawson has “merged camp and expressive ambiguity, tongue-in-cheek with seriousness.” The beaded bar top now sits in sections in the studio, awaiting a new home. “Strippers danced on that,” Lawson says, smiling. “Lord, all kinds of things . . .”

Up a flight of circular stairs, Lawson leads you into his “think tank,” an aerie overflowing with beads: buckets and boxes of them, spilling out onto the floor in rainbow heaps.

Two Madonna figurines await beading, and Lawson has begun the bead frame for a new work. Huge, beaded dragonflies dominate another unfinished work, and a happy blond mannequin of a little boy in a cowboy suit of lights stands guard in a corner. His portfolio includes many of his pen-and-ink drawings, representing untold hours of work, “which is where I learned the patience to do the bead paintings,” he said. “It prepared me.”

Lawson came to Louisiana State University 16 years ago on an art scholarship after attending Plymouth College in England, where he studied landscape and design. “I liked LSU,” he said, “because it gave me the feeling that it was OK to experiment, which was something I didn’t feel in England. “Over here, I’ve kept pushing my work in new directions. I’ve gone off in quite a few, shall we say, mis-directions, as well. Like I’ll sit and look at ‘The Garden’ and think, ‘I wonder what that would look like on acid,’ but you know what? I don’t know if it could compare with what these things look like by candlelight; they take on a whole new life!” Lawson recently married Aimee Michel, director of the Shakespeare Festival at Tulane and one of local theater’s most visual directors. Her collaborations with designers result in productions as memorable for their look as for the clarity of language. “We met a long time ago in England, fell in love at first sight, but I guess it took us 14 years to figure it out,” Michel said. The couple expects a child in January. “And the first thing I’ll do,” Lawson said, “is teach him how to use a glue gun.”

11/09/01

@ The Times-Picayune. Used with permission.

New Orleans Where Y’at Magazine

This article originally appeared in the September 2000 issue

“The Evolution of Dreams”

– by Myrtle von Damitz, III

They called him the toxic artist. He slammed gobs of oozing flashy plastic paint onto canvas,

then outlined demonic, leering, insulting figures. They writhed with glee in their bath of nauseating eye candy.

He hauled trash in from the street, contorted filthy objects into pleasing sculptures. Then he burned them and rearranged them. When they looked pleasing again, he left his little cottage in Sunshine, Louisiana and headed for the bars.

John Lawson’s affinity for toxicity is well known. His reputation has rested on illusory inspirations for many years. He blessed his Muse as he exchanged portraits for pitchers of beer. He communed with the Higher Spirit as chemicals and poetry raged from his tongue, and fingers fell into an abyss of expressioned madness that was considered inspired and prolific art.

Lawson had sought refuge in Sunshine; an old man from Baton Rouge told him about the cottage. While there, he also sought out the natural inspirations of the cypress swamps and fishing villages around Spanish Lake. Fisherman bought his figurative swamp landscapes. He brought his portraits of horseman chasing Mardi Gras chickens to Ed Weigand’s Bienville Gallery in New Orleans, where he showed every two years. According to Lawson, Weigand was a pioneer in New Orleans by showing Abstract Expressionist and Modern Art.

Weigand encouraged Lawson’s experimentations. Through the Bienville Gallery, Lawson met underground art king of New Orleans, Clint Peltier. “Clint and I had a strange relationship,” he muses. “He worked several nightclubs and most other people would try to kiss his ass.” The two artists became friends, bonded by mutual respect and the kinship of the netherworld party-land of New Orleans. “Clint would seek me out while I was wandering around in the swamps when he needed paintings or objects for a new club. I’d go back to Sunshine, pick up some pieces, and haul them down to New Orleans. After a while I would get this message that the club had been raided or closed down and I’d have to go and rescue my art.”

Lawson was not meant to be an artist. The working-class couple that created him molded him for factory work. When he was young, however, he drew his dreams as he remembered them, cultivating the battle histories of toy soldiers and ghouls. (At night he roamed the no-man’s land between the army of the safe, readymade Order and irrational subconscious force of the Ugly.)

Lawson eventually moved to New Orleans and settled into a wobbly building on Dryades Street. He continued to paint and sculpt and seek inspiration at parties and bars. These days, if one doesn’t know John Lawson’s name, they know him by the many objects he’s covered with Mardi Gras beads, including grand pianos, shoes,

mannequins, and bathroom scales. Dryades Street is where he first started to use Mardi Gras beads in a collaboration on a piano. This was the instance of Lawson’s first blessing: “I went into the H&R Lounge where some Mardi Gras Indians hung out and showed some of the guys photos of the beaded piano. They told me ‘pretty good for a white guy’ and I went from there….” I think every artist in New Orleans has used Mardi Gras beads at least once. I just happen to have a blessing from the Mardi Gras Indians. I plan to push the limitations of those beads the entire time I live in New Orleans. As he says, it’s “indigenous material.”

Lawson does not take words or the meanings behind them lightly. He is a poet, after all, and everything he makes or writes is imbued with meaning. “Art,” he says, “is still classified with the need for attention. I wouldn’t say that my work is for the good of the people. It’s still at a stage where it is a battle with my ego. All art has a degree of ego to it.” Often Lawson will take as a personal affront incidents that most people would take for granted in a corrupt society (or an absurd world).

In Baton Rouge, he rallied against David Duke’s political thrusts. At other times, he and another LSU friend followed trains transporting chemical waste to the end of the line (Carrville and the infamous cancer alley). They tried to expose what they saw to the public. However, Lawson says, they “couldn’t change the system, short of derailing a train. If you walk around those chemical plants they’ll arrest you.”

Lawson’s one way of calling attention to sneaky corruption and sanctified lawlessness was to express his outrage in his artwork. Thus the Toxic Artist, nourished by all the chemical components offered by Louisiana. “I hoped to gain a sense of sanity by being a radical,” he says. When he moved to Dryades Street, New Orleans was at the height of her great murder splurge of the ‘90s. “The violence was out of hand,” Lawson recalls. “This was just before Marc Morial’s first term, and there was this ‘white-flight’ thing — no one really caring or knowing what to do…. There was very little (political) organization. Then this little kid I knew was mowed down by a semi-automatic. I painted a mural for him on Magazine Street, and was then exposed to that neighborhood and what was going on, and that’s when I started building children’s coffins.”

“This city is a haven for artists,” says Lawson, “and one haven is Barrister’s Gallery, another is the Audubon Hotel.” Whenever he came to New Orleans, Lawson paid a visit to Barrister’s Gallery. Owner Andy Antippas first knew him as a part of “this group of kids that would come down from Baton Rouge to party in New Orleans. He could have become completely lost, but he managed to find some way out.” Lawson was drawn to Barrister’s for the inspiration. “It’s like a living museum,” he explains. In the tiny space on Royal Street (as even now in a cavernous warehouse in Central City), was a forest of African statues and masks, an aviary of beaded Haitian flags and Mardi Gras Indian costumes, and a multiplying bestiary of outsider art pieces. Artists overwhelm and absorb the visitor. Lawson could not shake off the magic dust or his current obsession with beadwork. Lawson’s coffins made appearances at Barrister’s, as well as his first beaded objects. “His beadwork,” explains Antippas, “reflects the ethnographic material in the gallery.” He worked over a skull in ruby red, and Antippas commissioned him to bead a fish for his two daughters, Artemis and Athena.

“I think his mannequins are his best pieces,” says Antippas. “There’s a certain quality of satanic camp about them. He has a knack for creating a satirical play on common themes. The mannequins look like little mythological creatures — like satyrs or fawns…they look sinister.”

The problems Lawson first encountered with the use of Mardi Gras beads have since faded. “He wasn’t sure if he wasn’t just doing craft,” says Antippas. “I think now he has transcended those problems.

Lawson’s crossover from paint to plastic beads parallels his crossover from Toxic Artist to Non-toxic Artist. The change came slowly, but had its roots in his immersion into the unpredictable world of the Audubon Hotel. After moving around, Lawson finally landed at the notorious Hotel, an underground Mecca. Clinton Peltier and John Spradlin conspired to transform the old seaman’s refuge into a 24-hour artist party refuge. Non-stop stimulation. When Lawson moved in, he accented the rough atmosphere with luminous and bizarre sculptures. He sanded floors, painted walls, and organized artistic mayhem. “Here came this guy with this BIG PERSONALITY. His initial contributions were important to the early days of the hotel. For a time there we called him the Den Mother; he was not a wallflower,” proclaims Spradlin. Spradlin and Peltier gave Lawson an open bar tab, and Lawson used the juice to fuel his work on his first beaded mannequins.

“Peltier had commissioned these three mannequins, and was going to give them to Spradlin. Peltier passed away before I was finished,” Lawson recounts. “When I was finished, I showed them to Spradlin, and told him the story.” Spradlin purchased the mannequins and from this point he says, “John became a very dear friend. He started talking about wanting to upgrade his whole life, start saving money. He was living art. He realized that he deserved the attention. He knew his work was wanted.”

Lawson considered the detriments of drinking and all the other forms of stimulation that kept him reeling from moment to moment, in ecstasy and at the edge of death. “You can only end up at Charity Hospital so many times before your luck runs out….” Instead of opening new, magical doors for him, his illness was getting in the way of his work. While at Audubon, Lawson refined the craft of assembling Mardi Gras beads: he found that the perfect glue was industrial strength and non toxic. The raging chemical man had refined his elements.

With help and advice from Spradlin and Antippas, Lawson got it together enough to move into an apartment in the French Quarter. Although he used to work construction jobs to keep up, today Lawson has his hands full with commissions. He is slowly working to fulfill his secret ambition of meticulously covering every inch of the French Quarter with Mardi Gras beads. “His work is so unique, so clever, so well done,” gushed patron and friend Lee Madere, who works out of his law office/bed& breakfast/gallery at 842 Camp Street. Madere owns three mannequins (in a series nick-named “Buster Brown”) as well as a beaded guitar, space ship, and bathroom scale.

“When people come in off the street, they look at these pieces and they feel good — safe and warm!” Madere continues. “Their reaction is not visceral, not intellectual. They smile, whether they think about it or not. They’re touched in a primitive way.”

David Favert, owner of the Quarter Scene Restaurant on Dumaine and Dauphine, fell in love with a portrait of Frida Kahlo that Lawson beaded onto a panel.

“There is a higher power. Life force is my higher power, in the universe, in the world. I don’t understand or wish to know what drives that. That force is stronger now and I can push myself even more. It manifests itself in everything I touch. I’m more interested in working with what I have. I’ve been humbled. The biggest thing I’ve had to accept is that drug inducement is a limited form of inspiration. It’s the ultimate power an artist can have. I humbled myself with the process of creating the work. I push it as far as I can, so you can look at Johnny’s piece and hallucinate for three seconds or more.”

As for imitators (and they are out there): “Their work will fall apart, because they haven’t been blessed by the Mardi Gras Indians.”

– by Myrtle von Damitz, III

John Lawson: The Hieronymus Bosch of Beads

What many people would regard as junk is, for New Orleans artist John Lawson, a “natural resource”—and a compelling artistic medium. A native of Birmingham, England, he uses Mardi Gras beads to bedeck all manner of objects–pianos, bongo drums, shoes, bones, mannequins, skulls, even antique bathroom scales–with intricate, visually intoxicating tableaux. It all began with a hallucinogenic Mardi Gras trip in 1984.

Read the rest of the article at: mardigrastraditions.com/john-lawson

It’s an Incredible Medium

By Bill Sasser, Gambit Weekly, New Orleans

February 13, 2001

“Originally I was doing paintings and black-and-white drawings, but ran into the dilemma of how I wanted to paint and stopped for a long time,” says Lawson, who collects his raw materials after parades on St. Charles, enough to fill five large plastic garbage bags in a season. “I feel I’m experimenting with how you see a piece of art – similar to Haitian sequin art, but I’ve expanded the subject matter. I still draw and sketch, but I love using beads – it’s an incredible medium.”

Using a hot glue gun, Lawson spends countless hours covering every square inch of an object in beads, creating artwork that is becoming a familiar sight in bars, restaurants and art galleries across the city. Over the past five years, he has beaded everything from mannequins to bar tops to bathroom scales. One of his beaded plaster skulls was featured as part of the house decor in MTV’s Real World.

His most ambitious canvasses are a series of five pianos, including a Baby Grand “Grand Piano” topviewthat he beaded in a jazz motif for a new Brennan’s restaurant in Los Angeles.

– an intricate mosaic of voodoo-inspired imagery centers on a pair of demon eyes hovering over the keyboard. “The magic is being able to use the beads like paint,” says Lawson, an accomplished landscape painter who taught himself how to create such flourishes as shadowing and depth in his beadwork. “It takes skill and imagination and a lot of patience to make it look good, but it’s an incredible palette.”

That his beadwork is art, rather than craft, is supported with the blessings of his potentially harshest critics – the Wild Magnolia Mardi Gras Indians.

That his beadwork is art, rather than craft, is supported with the blessings of his potentially harshest critics – the Wild Magnolia Mardi Gras Indians.

After I beaded my first piano, I took some photos and went into the H&R Lounge, where some of them hang out,” he remembers. “They said, ‘Pretty good, for a white boy.’”

Mardi Gras beads are one of many artistic departures for Lawson, a native of Suffolk, England, who came to Louisiana 15 years ago to study landscape architecture at LSU. Graduate school didn’t last, but it set Lawson on an odyssey that has taken him through the many labyrinths of the New Orleans’ art scene.

After living out in the swampy country, Lawson eventually started selling paintings in New Orleans and moved here after successful shows at Ed Weigan’s Bienville Gallery. Weigan introduced him to Clint Peltier, an artist and underground art entrepreneur who revived the Audubon Hotel as a bohemian refuge. Lawson decorated the bar with his artwork and still keeps studio space at the hotel. He also started hanging out at Barrister’s Gallery, where he remains inspired by Andy Antippas and his stable of folk and outsider artists.

Lawson took a turn into the lighter, Carnivalesque side of New Orleans five years ago when he joined another artist in beading his first piano, a New Orleans “honky-tonk” upright that their patron had rescued from a bar in Bywater before the building was torn down.

“These pianos were built back in the 1920s, using cheap wood that was actually desirable in New Orleans, because they wouldn’t warp in the humid weather,” he says of his Tom Waits tribute piece. “It was a piece of history that we saved and turned into a piece of art.”

Inspiration for his beadwork usually comes from the indigenous zeitgeist of New Orleans, and netherworlds like the Audubon Hotel. Critics have called his panel installation topping the hotel’s bar his most accomplished work: a 53-foot-long mosaic titled The Garden of Earthly Delights that mixes portraits of Audubon denizens with images from the master work by Hieronymus Bosch. “New Orleans is a place where people come and just go with it,” he says. “I’m good friends with the Wild Magnolia Mardi Gras Indians. I have friends in the Garden District, in Central City, in the French Quarter. Now people say I’m leaving my own mark on the culture.”

By Bill Sasser

The Lighter Side of Vice

ART REVIEW By D. Eric Bookhardt

WHAT: The Vices: Works by John Lawson and Julie Crozat

WHEN: Through October

WHERE: Barrister’s Gallery, 1724 Oretha Castle Haley Blvd., 525-2767

I don’t know of any such polls taken here in New Orleans, but it seems fair to say that Catholicism, and Catholic schools, have had some influence. Like Rio, or Havana in the old days, this place can be both very Catholic and yet very pagan, holding traditional views of sin while being unusually tolerant of sinners. It helps to be a native to fully appreciate this, and Julie Crozat, a graduate of local Catholic schools, puts a somewhat local spin on sin in her realistically rendered oil paintings. Gluttony depicts a fat lady in bed with dreams of ice cream, cookies — even a box of McKenzie’s doughnuts — dancing in her head. She sleeps in the nude, and if this is her version of a wet dream, it’s a distinctly gluttonous one.

Envy is also dreamlike, and the figure is also nude, but unlike the big lady, this babe is sleek and wide awake as she engages in a personal ritual of sorts, suggested by a swirl of tarot cards and voodoo dolls shimmering in the candlelight. She’s a redhead with trouble blazing in her pale green eyes, and those voodoo dolls are a dead giveaway that she’s unhappy with somebody. Greed is a more cinematic view of a sleekly attired babe who shares her bed with stacks of greenbacks. A pale-eyed blonde with a slim body and full lips, she has the pointedly blank look of a movie starlet, the sexy empty screen on which fantasies can be projected, and it hardly matters whether she’s from Hollywood or Metairie.

Crozat’s flair for luridly stylized spectacles is evidenced in her severed head scenes such as Anger, in which a prim woman holds the startled looking head of middle-aged man (Crozat’s husband, artist Michael Wilmon), while clutching a bloody knife with her other hand. The Sins of Salome is loosely based on the Biblical tale of Salome’s demand for John the Baptist’s head on a platter, only this Salome is a ’60s strumpet with candles, incense and Jimi Hendrix LPs, and the severed head (Wilmon again) shares a platter with a freshly rolled joint. The only virtue painting, Redemption, is of a distraught blonde with hands clasped in prayer. Rendered in shades of gray, it lacks the colorful flair of the others, perhaps revealing why Crozat focused on Vices in the first place. In true local fashion, her view is critical yet celebratory.

Although John Lawson is not a native (he’s a Brit), and even though his work is much more abstract, local sensibilities prevail nonetheless. That is because Lawson is a bead artist — as in Mardi Gras beads — and if Avarice, his 3-by-5-foot melange of bunched and patterned beadwork, depicts nothing identifiable, its sheer tacky opulence is sure to induce “throw me somethin'” echoes in the skull of anyone who sees it. And that, of course, is what avarice is all about.

Others are more tangential. Pride features a mannequin sitting on the floor amid a jumble of multicolored beads, and it seems like a stretch to say that this represents Icarus, the mythic figure who fell to earth after flying too close to the sun, but here again the beads convey a sense of something once high-flying, now grounded. In fact, Lawson says his work is really all about decadence and its importance as a source of the life force. His “squiggle” drawings, multicolored crayon abstractions not unlike his bead sculptures, employ the wit and wisdom of Baudelaire, Patti Smith and Johnny Cash among others, and, like Crozat, Lawson sees decadence as part of the color spectrum of the broader pageant of life — the rich black earth from which straight green shoots burst forth in the spring.

February 3, 2004 – Article from Gambit Weekly

Gambit Weekly – Disco Donnie

The Daily News of Newburyport, Mass. and Sonya Vartabedian

Artist draws a bead on New Orleans

For John Lawson, the highlight of New Orleans’ annual Mardi Gras begins long after the last parade rolls down St. Charles Avenue on Fat Tuesday.

It’s in the aftermath that Lawson takes to the streets in search of discarded Mardi Gras beads tossed by masked revelers. The multicolored strands strewn around roads, sidewalks and grassy provide the makings for his unusual art.

Lawson is known as the Hieronymys Bosch of Beads, a reference to the famed Dutch artist. While others have incorporated beads into their artwork, Lawson takes the practice to new levels.

He has covered five pianos — three grands and two uprights — in beads, leaving just the black and white keys and foot pedals free of embellishment. He has designed intricate portraits of New Orleans folk artists and street people bead by bead, and taken a more free-flowing approach to massive abstract designs dripping in colored strands.

“His work is just funky,” said Karen Dardinski, director of the gallery at Newburyport’s Firehouse Arts Center, where two dozen pieces by Lawson are on display for the month.

Lawson’s treasure trove of beads was one of the few possessions that survived the wrath of Hurricane Katrina last year. He and his wife, Aimee, who is local author Andre Dubus III’s cousin, lost their home and his adjacent art studio to the storm. They have been living from place to place since, staying with family and friends in New York and elsewhere.

Fortunately, much of Lawson’s artwork was unaffected by Katrina. In the spring of 2005 after finishing an exhibition at the Sundance Film Festival, Lawson had his artwork shipped to New York City, where it was safely stored in basements of galleries and on the walls of friends’ apartments when the hurricane struck. Twenty years worth of drawings, sketches and diaries inside his home did not fare as well, however.

A native of Birmingham, England, Lawson came to the United States to study landscape architecture at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge in the early 1980s. He remembers being at a friend’s house where a guy was playing honky-tonk piano and being struck with the image of the grand encased in beaded necklaces.

“Right there, the seed was kind of planted,” he said.

A few years later on post-Mardi Gras stroll, he was mesmerized by the strands of beads littering St. Charles Avenue.

“The sun was reflecting off the beads,” he said, “and I thought, ‘Wow, this is interesting.'”

Every year since, he has spent hours in the aftermath of Mardi Gras filling large trash bags with his booty.

His pianos — which took about three months apiece to complete — include a grand bearing a portrait of New Orleans pianoman James Booker on its lid. Another catches the eyes of diners at a Disneyland restaurant. But pianos aren’t his only canvas. He has covered high-heeled shoes, mannequins, bongo drums and even antique bathroom scales in beads,

Lawson said his large-size portraits are a testament of the tapestry of life in New Orleans and the people he has encountered there. They range from homages to Louis Armstrong to his New Orleans folk artist friends Herbert Singleton and Roy Ferdinand. The designs are a window into their souls, with images depicting Ferdinand’s militant philosophies and Singleton’s modern-day interpretations of the Bible.

He’s even paid tribute to “Ruthie the Duck Lady,” a streetperson in the French Quarters whom he first encountered when she came roller-skating into a local bar wearing the wedding dress she was supposed to get married in 30 years ago. The wedding never took place. When Ruthie isn’t decked out in her wedding dress, she can be seen accompanied by her favorite duck.

His abstract pieces feature wild, swirling patterns of beads affixed to wood panels

Working with beads has been a trial and error process that he’s refined over the years. Starting from a carefully-mastered sketch, Lawson has developed a formula working from the center on out, using a highly durable, nontoxic glue and a glue gun to affix the beads to the panels.

“The reason you don’t see a lot of artwork using beads is they’re hard to work with,” he said. “It’s not easy. I make them look easy.”

In addition to beads, Lawson also works with toys, plastic figures and other trinkets and baubles found on the streets or passed on by people. His mixed-media creations, he said, offer a surrealist’s approach to 21st century ideas, reflecting his opinions of today’s political climate. They include a modern take on “American Gothic,” pieces titled “Paradise Lost,” “War of the Worldz.com” and others.

“The children’s toys are just a decoy to draw you in,” he said.

Collectively, Lawson sees his work as a reflection of the living spirit that exists throughout New Orleans. He’s still processing the effects of Hurricane Katrina, but eventually hopes to draw from the experience as inspiration for new works.

“I want to examine every aspect of it, the loss, the anger,” he said. “There are so many human conditions involved when disaster strikes.”

But Lawson isn’t interested in focusing only on the dark and miserable side of Katrina.

“It’s one of those situations that’s rather complex,” he said. “One of the beautiful things about New Orleans is it does have the ability to laugh at itself. Definitely, one of the themes of New Orleans is humor. I don’t want to start working on them until I’m confident that humor and whimsical attitude can come out. … I don’t really like the obvious.”

What: “Homage to New Orleans,” an exhibit of artwork by New Orleans artist John Lawson, who incorporates recycled Mardi Gras beads into his designs.

When: Through March. A combination artist’s reception and fundraiser for Lawson and his family is being planned for the end of March.

Where: Firehouse Arts Center, Market Square, Newburyport.